In 2012 Orchard House celebrated it's 100th anniversary as a museum. There were many events held that year to celebrate. For one of these, Pulitzer Prize winning Eden's Outcasts author, John Matteson, spoke to Orchard House supporters about the personal connection he developed with the House as well as the "incredibly generous spirit" that many who visit feel when they are here. We wanted to share the following excerpts from that talk and highlight some of the reasons we are embarking upon our new documentary.

|

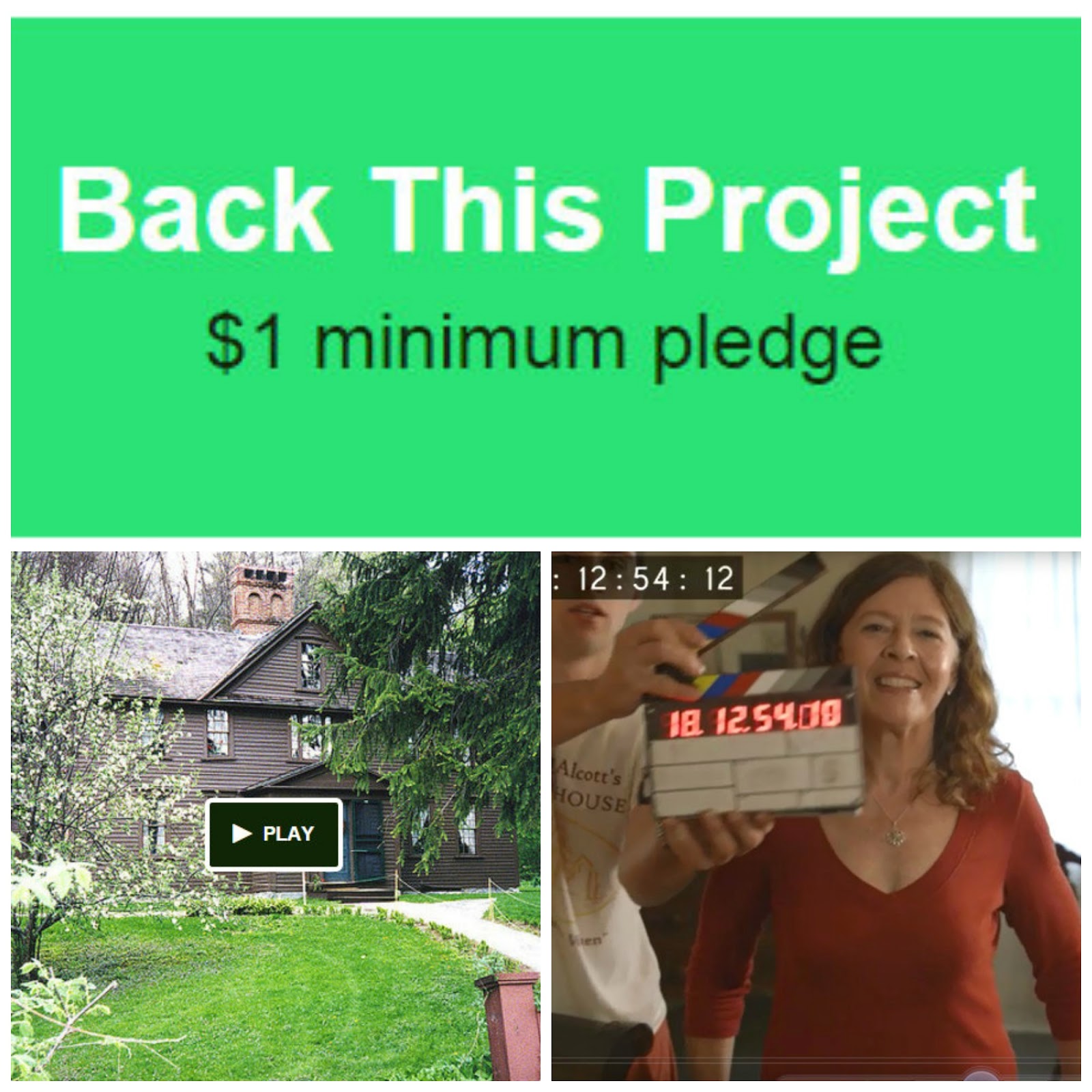

From our Kickstarter Campaign Video - John Matteson in

Bronson's Study

There are very few dissatisfactions that I can think of that go with being a biographer. One of them is the fact that your editor and your agent very seldom want you to write two books about the same people. Much as I would have loved to spend a good deal longer in Alcottland, the push was on for something different and, hence, as you know, I have spent the last four years intently focused instead on Margaret Fuller. And therein lies a fascinating comparison. . . quite honestly the experience hasn’t been the same, and I have been asking myself why. Some of it may have to do with the fact that there’s nothing to compare with the giddy experience of being a first time author. Perhaps something more of it has had to do with the personality of my subject. Louisa May Alcott’s humor, her vitality, and her loving insights into the human condition make her an incomparably appealing person with whom to spend four or five years. These might have been partial reasons why Eden’s Outcasts was a uniquely fulfilling project, but neither of them is the reason. I truly believe that the reason why writing about Margaret Fuller was more challenging – the reason why it was so much harder to bring her up closer to my imaginative eye —was that, unlike the Alcotts, she has no accessible public place that is particularly hers: no living shrine that is sacred to her memory. . .

The epilogue of my biography of Fuller is called “Margaret-Ghost,” which is a description borrowed from Henry James. It is singularly appropriate for her. Without a place where people can go to learn about her, to see her belongings and where she slept and ate and wrote, one feels that she is farther away, almost but not quite beyond the field of our magnetism, resistant to our poor power to call her back. We have letters galore, a few journals, and handful or two of images, but she can never be present.

It was from this same fate of almost irretrievable remoteness that Louisa and the other Alcotts were rescued a century ago, when the foresighted founders of the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association saved Orchard house from destruction and set it on the path to becoming the thriving historic site that it is today. Knowing Orchard House as well as all of you do, I am sure you find it no mere flight of imagination to suppose that a building can possess a soul. One’s appreciation need not be for history; it need not be for literature. One need only understand the preciousness of love and family to know that Orchard House is more than boards and nails, greater and more precious than paint and plaster. It is a place that welcomes, and it is one that inspires.

My own association with Orchard House began when I was in the early phases of researching and writing Eden’s Outcasts. As you may know, Eden’s Outcasts was my first book, and back in 2002 and 2003, I was taking my very first steps toward authorship. If you had asked me then to offer any good reason why anyone should take any great interest in me as a writer, I would have been stumped for an answer. Astonishingly, though, that didn’t seem to make any difference to anyone at Orchard House, and certainly not to our wonderful executive director, Jan Turnquist. She immediately granted me full, behind-the-ropes access to the entire house and even conducted me down to the basement to discuss the then-intended renovations of the foundation. Then she took me to lunch. She made me believe that I was just the right person to be writing Louisa’s and Bronson’s biography, and she kept on making me feel that way, straight through to publication. What a remarkable woman, I thought then, and I think so now. But what I did not realize at the time was that Jan was really just reflecting in concentrated form the incredibly generous spirit that pervades the entire organization that makes Orchard House go. It is a spirit that began with the Alcotts themselves, and, remarkably, it continues to be made manifest in those who preserve the Alcott legacy. Private person that she was, it might have taken Louisa quite a while to get used to the steady stream of admiring visitors who now make their respectful way through her father’s house. However, if she were able to see the welcoming spirit with which today’s custodians have made the house available to the public, the careful fidelity with which they preserve the authenticity of the past, and the spirit of goodness that touches everything that is done there, I think she would be deeply proud.

Now, I should freely confess that I am a world-class sap when it comes to matters like this one. I should admit that, in 2005, when my wife Michelle and daughter Rebecca took me to see the Little Women musical on Broadway, I was sobbing helplessly before the curtain went up. So I may not be the best person to consult regarding the way a person of average sensitivity approaches Orchard House. But, for whatever it may be worth, I have walked along the Lexington Road from Concord’s Town Center with an anticipation and an upwelling of emotion that is barely describable. I have felt something that is probably quite close to the sensation Emerson recalled when he wrote of being “glad to the brink of fear.” I suspect that, as you have walked that last gentle curve before the Alcott property comes into view, many of you have felt the same involuntary tightening in your throat, the same hint of moisture in the corners of your eyes. If you have, then you know just what I mean when I call Orchard House one of the most precious places on earth. If you haven’t ever felt those feelings, then I encourage you to take that walk again, sometime very soon. For unlike the ghost of Margaret Fuller, who wanders always in search of her true home, the spirits of the Alcotts are safe at home and always waiting to receive us, thanks to all the marvelous people, in 1912 and in 2012, who have made certain that they need never stray.

.jpg)